When a project idea first emerges, it’s common for the originator to share early thoughts with colleagues – seeking support, insights, or technical expertise. The concept develops organically and eventually receives the green light to move ahead.

At this point, the traditional approach is to bring in a project manager, engineer, or director to implement the idea: managing cost, schedule, and resources to ensure smooth delivery.

However, one area often neglected is scope definition. Clients and stakeholders have usually been immersed in the idea for months, sometimes years. In their minds, the scope is obvious. But what’s clear to them is not always clear, or realistic, to the delivery team.

A Classic Case of Poor Scope Definition: HS2

A well-known example is HS2. The ambition was simple: “We want the fastest high-speed trains in Europe and to cut the London–Birmingham journey time by 20 minutes.”

To achieve this, designers needed as much straight, level track as possible, driving the need for extensive bridges and tunnels. Costs escalated rapidly. Yet amidst the drive for “the best”, a crucial challenge went unvoiced for too long:

“Do you really want the fastest line in Europe if it also becomes the most expensive per kilometre?”

HS2 is an extreme case, but the underlying issue is common: a desire for a world-class solution without the budget, time, or resources to support it.

The Role of the Project Manager

One of the project manager’s most important responsibilities is to define and agree the Project Charter, which includes:

- Scope (and what is not in scope)

- Project structure

- Justification / Business case

- Timescales

- Budget

1. Scope Definition

Interviewing the client and their subject-matter experts is essential. Alignment is critical: everyone must agree on what the project will deliver and what it won’t.

The scope definition should include:

- A clear project description

- Agreed requirements from all stakeholders

- Success criteria for both delivery and operational performance

- Project justification and financial rationale

- Identification of all stakeholders

2. Project Structure

Next, the governance and resource structure must be defined:

- Who is the main stakeholder?

- Is there a project board?

- What resources (engineering, operational, SME) are required?

- Do we need recruitment or a dedicated start-up team?

A helpful tool here is RATSI: to define each persons roles and responsibilities.

- Responsible – who delivers the project

- Authority – who makes go/no-go decisions

- Task – who owns specific project activities

- Support – who provides assistance

- Inform – who is kept updated

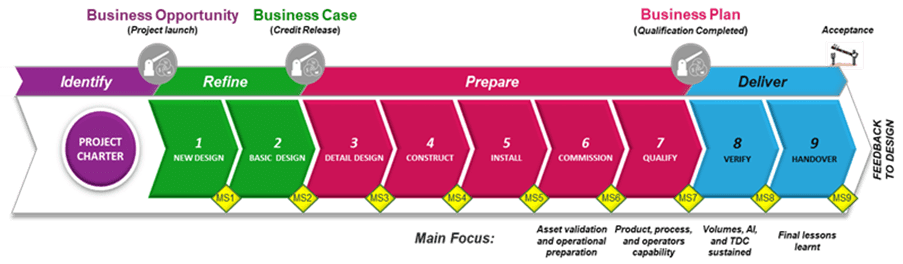

Large or complex projects may also include gated milestones, each with required deliverables before progressing.

3. Project Justification

A robust business case is essential. Regular health checks should assess whether the project still makes sense financially and operationally. Taking the latest budget and comparing it to the latest savings.

4. Timing Plan

Start simple – key milestones only, then evolve it as more detail emerges and decisions are made.

5. Budget

Initial budgets are often high-level, based on early design inputs. As the project matures, the budget should develop and become more accurate.

Both the schedule and budget must be locked once credit release occurs and may only change with approval from the Authority identified in the RATSI.

Closing Thought

A well-structured project dramatically increases the likelihood of success. But if your project isn’t running smoothly, or you’re unsure whether the foundations are solid, feel free to contact me. I’d be delighted to conduct a project review and help get things back on track.

Leave a comment